The death of Jean-Luc Godard at the age of 91 marks the end of an era, not only of a certain modernist tradition of auteur cinema, but also of cinema as a primary vehicle for existential and historical truth. Marguerite Duras considered him the greatest catalyst in cinema, and no other film-maker grasped better, or exploited more, the potential of sound and image. His prodigious oeuvre and the staggering range of forms and formats in which he worked have redefined our understanding of cinema as an art form and cultural practice, transforming the way we look at ourselves and the world.

Godard came to prominence in the early 1960s as part of the French New Wave, the most important national film movement of the 20th century. These film-makers – many of them critics for the journal Cahiers du Cinéma – believed passionately that a film’s visual style is an authorial signature reflecting the director’s personal, creative vision. Inspired by American directors such as Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray and Orson Welles, the Italian neorealist Roberto Rossellini and French film-poets such as Jean Vigo, Jean Cocteau and Jean Renoir, they attacked the studio-bound French “cinéma de qualité”, which they believed had become stagnant, relied on uninspired scriptwriters and established stars, and stifled personal creativity.

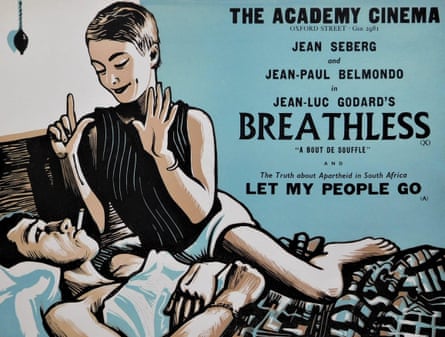

François Truffaut’s narrative-driven Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) had conquered Cannes in 1959, but it was Godard’s first feature, the formally inventive and effortlessly hip À Bout de Souffle (Breathless, 1960), starring the then unknown Jean-Paul Belmondo opposite Jean Seberg, that changed the course of cinema. The film was shot fast and cheaply like reportage in natural light, on the streets and in hotel rooms. It flouted continuity editing and employed jump-cut and to-camera techniques, along with obsessive close-ups, to create spontaneity (a film should have a beginning, middle and end, but not necessarily in that order, Godard quipped). It also played self-reflexively with genre (especially American gangster movies and film noir) and continuously referenced recent Hollywood films and figures such as Humphrey Bogart, as well as painting and poetry.

The entire soundtrack, with Godard’s impudently witty dialogues punctuated by slang, was later dubbed and mixed with Martial Solal’s fluid jazz score. This was a dynamic juxtaposition of high art and popular culture and an original way to capture contemporary reality. It was also a raw statement of artistic freedom, and it set Godard on course to become the most individual and influential film-maker of his generation, known for axioms such as “cinema is truth 24 times a second” and “it’s not a just image, it’s just an image”.

Godard was born in Paris into a privileged Franco-Swiss Protestant family, the second of four children. His French father, Paul, a physician, owned a private clinic. His Swiss mother, Odile, came from a pre-eminent banking family, the Monods. His background was thus politically conservative yet also culturally enlightened (his maternal grandfather, Julien-Pierre Monod, was a friend of the poet and essayist Paul Valéry). Educated first in Nyon, Switzerland, “Jeannot” was not an academic child although he possessed a talent for painting and was a fine athlete and swimmer. Godard was a troubled and often contrary young man, and as his parents grew more estranged he was sent to the Lycée Buffon in Paris. There, his growing kleptomania reached dangerous levels, leading to his theft of first editions of Valéry from his own grandfather. He was found out and essentially disowned by the Monod clan, leading to a period of semi-bohemian drifting. He studied ethnology briefly at the Sorbonne in 1949.

Godard was by now frequenting film clubs in Paris, in particular the Ciné-club du Quartier Latin, and declared he was going to be the Jean Cocteau of the new generation. He met first Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol, and then, in September 1950, Truffaut, with whom he forged a close bond. He immediately regarded the cinema as his new home and family, with Henri Langlois, who curated inspirational screenings at the Cinémathèque Française, as a benign uncle. This is where, by his own admission, Godard learned about life. Such profound identification with the cinema, rather than pure arrogance, accounts for why he could later describe himself as “Jean-Luc Cinéma Godard”.

Under the pseudonym Hans Lucas, he began writing for La Gazette du Cinéma, founded by Rohmer and Rivette. These early articles matched the feverish, impulsive nature of his viewing habits and display his exceptional range of reference (filmic, literary, musical, critical), his fondness for wordplay and demand for aesthetic judgment. His first, highly polemical articles for Cahiers du Cinéma in 1952 championed Alfred Hitchcock and highlighted montage, thus setting him against the journal’s revered co-founder, André Bazin, who preached the “true continuity” of mise-en-scène. When the journal changed its outlook with Truffaut’s incendiary 1954 article, A Certain Tendency of French Cinema, which outlined the policy of auteurism, he refined his rhetorical critical style, producing articles that emphasised cinema as an intrinsically moral and democratic art.

After another bout of stealing in 1952, this time from the very coffers of Cahiers du Cinéma, Godard returned to Switzerland for a job at Télévision Suisse Romande, but his acquisitive hands again got the better of him and he was locked up. The threat of Swiss military service was now real, so his father had him transferred to a psychiatric hospital. His mother then landed him a job as a labourer on a dam under construction on the Dixence river, where he made his first film, a 20-minute 35mm documentary short entitled Opération Béton, with his own voiceover. On his return to Paris in 1956, he worked in the publicity department of 20th Century Fox. He also gained professional experience as an editor and writer of dialogues for the film producer Pierre Braunberger, who financed a string of playful shorts, including Une Histoire d’Eau (1958), which matched Godard’s sparkling literary script with images of recent floods provided by Truffaut.

Following the spectacular success of À Bout de Souffle, Godard retained his documentary cameraman Raoul Coutard and enlightened producer Georges de Beauregard but deliberately changed tack with Le Petit Soldat, featuring the Danish model Anna Karina, whom he married in 1961. So began the “Karina years”, one of the most productive periods of uninterrupted creativity in modern cinema. Filmed in 1960 in Geneva, Le Petit Soldat was a political thriller of agents and double-agents dealing with the Algerian war and depicted torture on both sides. Such ambivalence, typical of Godard, led to it being banned until 1963.

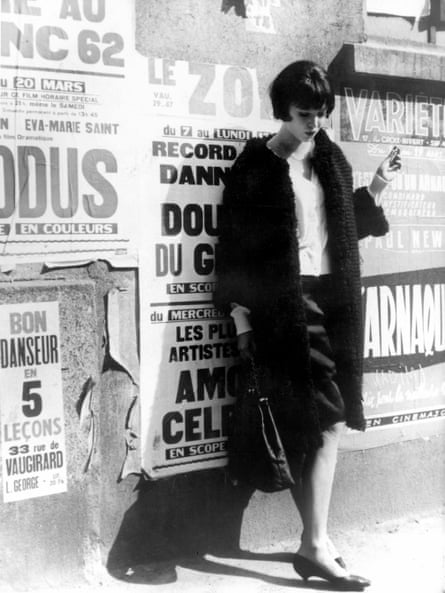

Karina’s radiant presence was captured in colour in the musical comedy pastiche, Une Femme Est une Femme (1961), then in Bande à Part (Band of Outsiders, 1964), a tender “suburban western” in which she dances the Madison with Claude Brasseur and Sami Frey. Vivre Sa Vie (1962), a cinéma-vérité study of prostitution, based on real sources, with Karina as the doomed Nana, also embraced scenes from Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, working-class chansons and a guest appearance by the linguistics philosopher Brice Parain, while drawing on the works of Edgar Allan Poe. It pushed the bounds of form by using live sound, denaturalised framing and a tracking camera as swinging pendulum. Godard pulled off this daring combination with a wondrous lightness of touch, although, as so often, the production had not been easy. He was sometimes moody, often remote, on set. Nothing was improvised, yet actors often found their lines rewritten just before a take.

After Les Carabiniers (1963), an uncompromising allegory about war (and his first flop), came the brooding, big-budget Le Mépris (1963), a potent mix of the classical and modern with its teasing use of Brigitte Bardot in a love triangle with Michel Piccoli and Jack Palance. Set in the deserted lots of the Cinecittà studios, where Fritz Lang (with Godard as assistant) is making a modern version of the Odyssey, it exudes Godard’s increasing pessimism that civilisation (including cinema) was nearing its end.

Une Femme Mariée (1964), an exemplary collaboration with the actor Macha Méril, revealed Godard as an acute observer of the pernicious effects of the new consumer society, while Alphaville (1965), starring a luminous Karina and shot at night in Paris in high contrast black and white with alternating positive and negative images, was a dystopian sci-fi vision of a loveless, computerised society of glass and concrete. This was also the new, dehumanising face of the fifth republic. Pierrot le Fou (1965), shot in bright primary colours and filters, reflected the volatile state of Godard’s marriage, which would soon end in divorce. It began with the director Sam Fuller defining cinema as “love, hate, action, violence and death, in one word, emotions”; it ended with the suicide of Ferdinand (Belmondo) by dynamite with a quote from Rimbaud.

Godard seemed unstoppable. With his mercurial intelligence and humour, his restless energy and curiosity, he proceeded by trial and error, criss-crossing different artistic fields and plugging into new intellectual and cultural currents with astonishing ease. Each film was conceived as a pseudo-scientific inquiry and as part of an evolving, all-encompassing project. What made Godard so special was his extraordinary sensitivity to beauty, form and gesture. He had a unique ability to alight on an object and, through framing, dramatise its material existence and plasticity. The multiple textures and ellipses of his work achieved with his regular editor, Agnès Guillemot, produced sudden flashes of often breathtaking simplicity and grace, and his ingenious use of signs, texts, and photomontages illustrated his exceptional skills as a graphic artist. He continually experimented with mutating credit sequences and intertitles and even designed his own trailers.

In 1965, the poet Louis Aragon hailed Godard’s ground-breaking collage technique in a famous encomium, “What is art, Jean-Luc Godard?”, and Truffaut himself now agreed there was a before and after Godard. In fact, Godard had become a cultural star and media phenomenon, in public dialogue with film-makers and writers such as Lang, Michelangelo Antonioni and JMG Le Clézio. With his persona of reserved intellectual in trademark black glasses, his mischievous smile and laconic provocations, he played the media as much it played him.

His influence abroad was immense, in particular on the new generation of European film-makers such as Bernardo Bertolucci, or Martin Scorsese, Brian de Palma and Robert Altman in America. Some on the left still regarded him as a disengaged dilettante flirting anarchically with big ideas. However, his next film in black-and-white, Masculin Féminin (1966), starring Jean-Pierre Léaud, encapsulated perfectly “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola”, the Americanisation of French life, and the new era of Vietnam.

The masterpieces kept coming. Deux ou Trois Choses Que Je Sais d’Elle, filmed back to back in 1966 with the cartoon-style faux-policier Made in USA and using the same crew, was his first fully realised fiction-essay. Featuring a serene Marina Vlady as a housewife moonlighting as a sex worker (“elle”), it decoded the Gaullist ideology of urbanisation in the new housing complexes being constructed in the Paris region (also “elle”). Godard was searching for – and finding – new, formal “complexes” uniting subject and object, capturing, for instance, the workings of the cosmos in a cup of swirling coffee.

La Chinoise and Week-end (both 1967) starred Anne Wiazemsky, a young student and granddaughter of the writer François Mauriac. Godard married Wiazemsky in July 1967. La Chinoise, with its revolutionary pop-art rhythms and anti-realist, degree-zero style, was a brilliant study of a Maoist cell in training, influenced by Brecht and Althusser and highly prescient of real events just around the corner. Week-end portrayed French society in a state of abject breakdown with apocalyptic scenes of destruction and cannibalism. It also systematically tore apart the very grammar of film and included the longest tracking shot yet filmed. The final caption read: “End of Cinema.”

In early 1968 Godard played an active role in the successful protests against the dismissal of Langlois from the Cinémathèque Française by the culture minister, André Malraux, to whom, just two years before, he had published a fierce open letter condemning the banning of Rivette’s film, La Religieuse. He was also instrumental in shutting down the Cannes film festival, and worked collectively during the events of that year on a series of anonymous one-reel ciné-tracts, one of which, known as Le Rouge (a collaboration with the artist Gérard Fromanger), recorded red paint bleeding across a representation of the French flag.

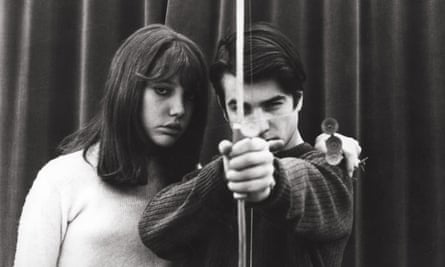

He then rushed to London to shoot the Rolling Stones in rehearsal, and Wiazemsky as an urban guerrilla, in One Plus One, a film over which he later came to blows – quite literally – with the producer Iain Quarrier at the National Film Theatre. He was briefly a globetrotter of revolutionary cinema, making trips to American campuses, Cuba and Canada, although One AM (One American Movie), which included interviews with the Black Panthers in Oakland, was never completed.

One of the slogans of May 1968 stated: “Art is dead, Godard can do nothing.” In fact, for the first time Godard was feeling out of step with the new generation and unsure about his artistic identity. It seemed the only option now left to him, as a self-declared Maoist, was to disown his bourgeois status as auteur and start over completely. With the militant student Jean-Pierre Gorin, he formed a small film collective, the Dziga Vertov Group, which attempted not simply to make political cinema, but to make films politically. The result was five extremely didactic films for European television, including Vent d’Est (1969), co-scripted by the student leader Daniel Cohn-Bendit, who also starred. Ironically, funding was ensured by the viability of Godard’s name, yet none of the films was broadcast. The sadomasochistic pranks acted out with Gorin in Vladimir et Rosa (1971), which mimicked the trial of the Chicago Eight, seem in retrospect more like escapist fantasies, though Gorin spoke later of his time with Godard as like a love affair.

Tout Va Bien (1972) was their attempt to reach the mainstream by employing politically engaged stars such as Jane Fonda as a journalist and Yves Montand as her husband, a former New Wave film-maker. This torturous film about class struggle in the fall-out of 68 caught the general mood of mourning for a lost historical and revolutionary moment. The accompanying short, Letter to Jane, a verbal assault on Fonda as a false revolutionary, was an act of viciousness on Godard’s part. Like a fanatical convert, Godard was squeezing himself dry in an alien political logic and working against his natural tendency to ambiguity and paradox – the very qualities that made his work so compulsive.

Godard had reached an artistic impasse and the group disbanded. In addition, the political tensions between Godard and Truffaut that surfaced during May led to an ugly and permanent falling out. After Godard’s attack on him for the “lies” of his 1973 film, La Nuit Américaine (Day for Night), Truffaut penned a long letter accusing Godard of being a duplicitous dandy and bully. This was the final nail in the coffin for the New Wave. Yet by now Godard – whose relationship with Wiazemsky had ended; they divorced in 1979 – had met a new partner, Anne-Marie Miéville, a pro-Palestinian French-Swiss gauchiste like himself who helped look after him following a near-fatal road accident in June 1971 that left him in a coma for a week. This experience changed Godard and allowed him to reassess his life. With Miéville he formed a small collective workshop called Sonimage – romantically conceived as a combination of her sound and his image – which they took to Grenoble to develop together.

This was the start of a new period of intellectual and emotional partnership on equal terms unlike anything Godard had experienced before. The two embarked on a series of pioneering experiments in film and video, including the essay Ici et Ailleurs (1974), born out of the ashes of a failed project with Gorin for the PLO, which provoked charges of antisemitism for juxtaposing the faces of Hitler and Golda Meir (Godard regarded himself as an anti-Zionist); Numéro Deux (1975), a rigorous deconstruction of sexuality and gender within the family; and two major television series about modern communications and human relations that constitute some of the most sustained theoretical analyses of the medium ever produced.

The couple moved in the late 1970s to Rolle, a small town between Geneva and Lausanne, to achieve their ideal of artisanal autonomy and harmony between life and work. This would bear fruit in such work as Soft and Hard: Soft Talk on a Hard Subject Between Two Friends (1985), one of several innovative videos commissioned by Colin MacCabe at the British Film Institute, in which they filmed themselves in their domestic routine discussing creative projects and questions of art, cinema and communication.

Sauve Qui Peut (la Vie) (Slow Motion, 1980), co-scripted and co-edited by Miéville with a pulsing electronic score by Gabriel Yared, marked Godard’s triumphant return to feature film-making. Starring Isabelle Huppert, Nathalie Baye and the singer Jacques Dutronc as his alter ego, Paul Godard (the name of his father), it was Godard’s second “first film” and the culmination of his recent video experimentation with slow motion. Shot by William Lubtchansky using a lightweight 35mm camera specially designed for Godard by Jean-Pierre Beauviala, the film included a voiceover sequence with Duras, illustrating his desire to engage directly not only with female discourse but also with his “number one enemy”, literature (“texts are death, images are life,” he memorably stated).

Passion (1982), which reunited Godard with Coutard as well as Piccoli, was a soaring tale of aesthetics, class politics and religion featuring tableaux vivants of the great masters. It inspired in turn Scénario du Film Passion, an even more extraordinary video short in which Godard demonstrates how Passion came into being. Next, in quick succession, came the dazzling Prénom Carmen (1984), which marked the first of several performances by Godard as a kind of eccentric professor; the controversial Je Vous Salue, Marie (1985), a genuine attempt by Godard with Myriem Roussel to explore the sacred and corporeal, though it was banned by the pope; and Détective (1985), a humorous take on the genre shot entirely in a Paris hotel.

This remarkable creative burst confirmed that Godard was one of the greatest exponents of sound. Before he had fragmented and rearranged the title music he commissioned from film composers such as Michel Legrand, Georges Delerue and Antoine Duhamel. Now, with the sound engineer François Musy, he was intermixing, recomposing and transforming “found” music (largely classical). In the late 1980s, he made contact with the music producer Manfred Eicher, head of ECM Records, who introduced him to a new set of modern composers, including Paul Hindemith, Giya Kancheli and Arvo Pärt, so providing the soundtrack to his later work.

Nouvelle Vague (1990), starring Alain Delon, was a ravishing paean to the Swiss landscape of his childhood that plays with the theme of revelation and the eternal return. It heralded an extensive phase of personal, historical and philosophical contemplation that engaged with themes such as age and exile, European history and memory, and art versus culture. The prevailing mood of these new, complex film-essays was elegiac, often melancholic.

Allemagne 90 Neuf Zéro (1991) was a meditation for television on the solitude of Germany following the fall of the Berlin wall, while JLG/JLG: Autoportrait de Décembre (1995) presented an intimate study of childhood, memory and loss. Other commissions included Puissance de la Parole (1988) for France Télécom, which made stunning use of video processes and speed; Le Dernier Mot (1988), a short historical study for television about the Resistance (now a central concern); a series of exquisite, dance-inspired video clips for the fashion company Marithé et François Girbaud; and (with Miéville) short pieces for Unicef and Amnesty International.

Godard still attracted an ardently loyal cinephile audience, even if in the UK his work was now barely distributed. He was also an automatic point of reference for French and American film-makers such as Leos Carax, Claire Denis and Quentin Tarantino, who emerged in the 1980s and early 1990s. However, he was now perceived by many critics and cultural commentators, in France and elsewhere, as an increasingly inaccessible and world-weary monstre sacré. He rarely left his purpose-built studio in Rolle except to collect his first honorary César, in 1987, and the prestigious Adorno prize in Frankfurt in 1995, or to act in Miéville’s films of the 1990s.

Yet all the works mentioned, as well as “lost” films such as the enigmatic King Lear (1987), were feeding into a monumental video project, Histoire(s) du Cinéma, which consumed Godard’s energies from the late 1980s to the late 1990s and evolved from a series of lectures he gave in Montreal in 1978-79. Only Godard perhaps could have conceived such an ambitious project – to produce a history of cinema in the very medium itself. Drawing on film archives, newsreels, photography, painting and animation, it brought together history, the history of cinema, and Godard’s own personal histories.

His principal thesis was that cinema had now come to an end, having fatally missed its appointment with the second world war (specifically the Holocaust) and thus failed in its duty to document reality. The video was both a celebration and work of mourning, and Godard’s pedagogical method of “historical montage”, which transformed ideas and the senses through ever more audacious juxtapositions, reversals and superimpositions, was the logical culmination of his long career in montage, formulated now in concrete terms as “thinking with one’s hands”. Histoire(s) appeared also in an art-book and CD version and stands as one of the great artworks of the last century, confirming the view of the critic Serge Daney that Godard was less a revolutionary and iconoclast than a radical reformer tirelessly correcting his own practice and cinema itself.

Godard continued to experiment with digital video. Éloge de l’Amour (2001), a tale of the Resistance, memory and exploitation, used sumptuous black-and-white photography to capture contemporary Paris, then, in its second half, the saturated colour of DV to depict a period three years earlier. Notre Musique (2004) crystallised his intense interest in Yugoslavia since the early 1990s, its central section “Purgatory” charting war-torn Sarajevo, where he played himself meeting writers such as Mahmoud Darwish and Juan Goytisolo.

He embarked also on a major multimedia project entitled Collage(s) de France for the Pompidou Centre in Paris, but after much work and planning fell out with the curator and the project was dramatically scaled down. When it finally opened to moderate acclaim in 2006 as Voyage(s) en Utopie, it resembled less an exhibition than a building site, with its minimalist, art brut-style installations and assorted mini-ruins.

Equally uncompromising was Film Socialisme (2010), a blistering indictment of western Europe’s military and colonial past in the Mediterranean where different kinds of video format are pushed at times to pixellated distortion. Conventional English subtitles were replaced with broken Navajo English and Godard provided six different trailers offering super-speeded-up versions of the complete film, thus demolishing the idea of the artwork as property. Now 80 and physically rather frail, he presented the film as his “last for the moment” and sold off all his assiduously maintained studio equipment.

He did not turn up to collect an honorary Oscar in 2010. Yet he continued to release bold, urgent and visionary works: Adieu au Langage (Goodbye to Language, 2014), winner of the jury prize at Cannes, which deployed makeshift 3D techniques to rethink the cinematic process; and Le Livre d’Image (The Image Book, 2018), a defiant act of collage and rupture which addressed head-on, as ever, the violence in the act of representation.

He is survived by Miéville.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion