Opinion: research shows that precarious work reduces political participation, increases inequalities and is detrimental for younger generations

By Ross Macmillan, University of Limerick and Leo Azzollini, Bocconi University, Milan

For decades, we have assumed that the type of work people do shapes political participation. For example, the nexus of "labour," working class identity and support for leftist parties has organised politics and political analysis for decades. Likewise, white-collar and managerial workers are seen to support for more conservative, right-of-centre parties. Workplaces in general have traditionally served as an arena for political socialisation that encourages participation. This is good for democracies in that it encourages people across the political spectrum to participate, which should have knock-ons for politicians seeking to represent the interests of broad swathes of populations.

However, the traditional assumptions about links between work and political participation needs to be re-thought. Recent years have seen radical changes in labour relations that call into question traditional ideas about work, labour, and politics. We have seen a significant growth in "precarious work", work that involves limited duration or no contract and is characterised by low control over daily tasks, little influence on the employment organisation, cyclical unemployment, and financial vulnerability.

Often characterised as "bad jobs," precarious work is increasingly prevalent as employers seek greater and greater flexibility in labour relations. While associated with a host of economic, familial, and health problems, our research indicates that precarious work also undermines political participation and increases political inequalities that are particular detrimental for younger generations and those with lower socioeconomic status.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Drivetime, Philip Boucher-Hayes and Della Kilroy report on precarious employment in Ireland

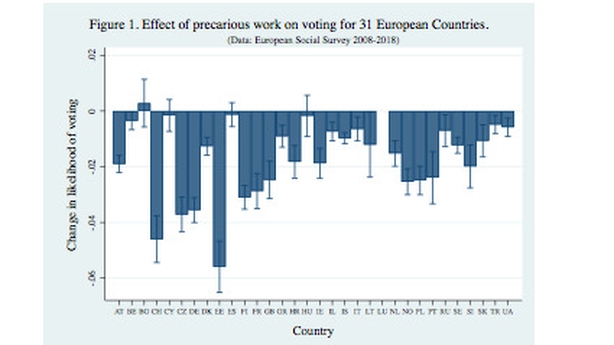

We investigated the implications of precarious work for political participation across a broad sample of 31 European countries. We measure precarious work simply as the number of different indicators that people report (ranging from 0 to 5). From many different angles, precarious work is bad for democracy.

To start, we asked if the likelihood of voting changes with increases in precarious work. Figure 1 shows the effect of precarious work on likelihood of voting across all countries studied. The pattern of negative effects is pervasive: precarious work reduces voting in 27 of the 31 countries surveyed. Using Ireland as an example, each additional indicator of precarious work decreases voting by just under 2%. In other words, those with high work precarity are 11% less likely to vote than those in non-precarious work.

In general, the negative effect of precarious work on voting is quite remarkable given variation in economic development, political systems, demographics, culture, and history across countries. The countries that buck the trend, including Bulgaria, Cyprus, Spain, and Hungary, constitute less than 9% of the total population of Europe. As elections all across Europe are often won or lost based on a few percentage points, the implications of precarious work for political outcomes are profound.

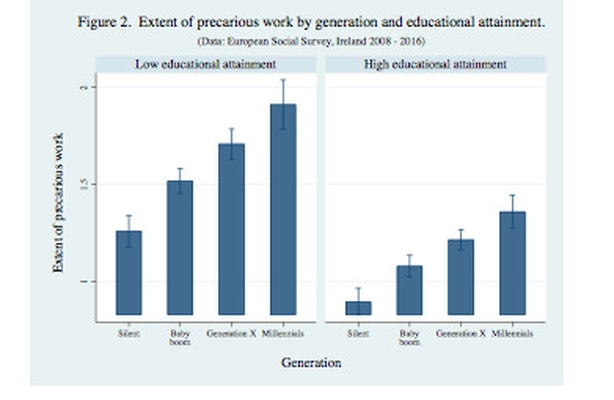

Yet, the story is more complicated than that seen with country averages. Focusing on the Irish context, we asked two further questions. First, who is most at risk of precarious work? The answer is quite simple: younger people and those with limited educational attainment.

Figure 2 shows the extent of precarious work broken out by generation and educational attainment. The former distinguishes the "Silent" generation (those born prior to 1946), the "Baby boom" generation (born 1946 to 1964), Generation X (born 1965 to 1980), and Millennials (born after 1980), while the latter distinguishes those with either only secondary schooling versus those with university degrees.

When educational attainment is lower (left panel), the extent of precarious work increases across generations, with Millennials having significantly higher risk than all other generations. Although overall risk is reduced, the same pattern occurs where educational attainment is high (right panel). Combining generation and educational attainment highlights accumulating disadvantage: risk of precarious work for Millennials with lower educational attainment is close to double that of both the Silent and Baby Boom generations with high educational attainment. For older generations, high work precarity is/was almost unheard of. For the youngest generation, it is increasingly the defining feature of paid employment.

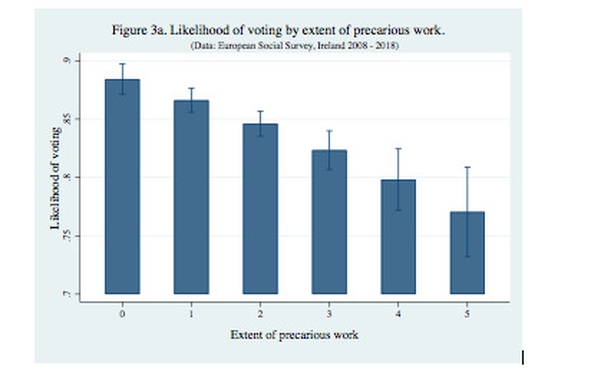

A second question is how precarious work influences likelihood of voting and figure 3a shows the overall relationship. For those in non-precarious work, almost 9 in 10 people (88.4%) reported voting in their most recent election. For those with high precarity, just over three-quarters (77.0%) reported voting.

A difference of 11% is not trivial: the 2016 Irish election saw Fine Gael 1.2% higher than Fianna Fail in the popular vote (25.5% versus 24.3%) and the 2016 US presidential election had numerous electoral districts where Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton were separated by one or two percentage points. Even the "landslide" victory of Boris Johnson's Conservative party in the UK in December 2019 was only an 11% difference in popular support. Although we do not know much about which political parties precarious workers would gravitate to, differences in participation that we highlight vastly exceed margins of victory for a large number of recent elections.

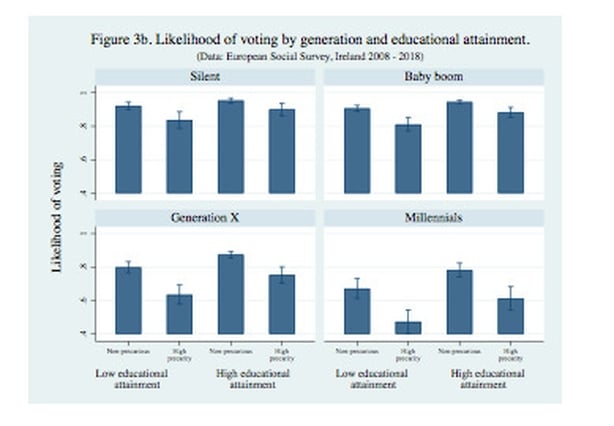

Perhaps, more important, overall differences mask the real political impact of precarious work due to its relationship with generation and educational attainment. Figure 3b shows the combined effects. Among the Silent generation, about 90% are likely to vote. Even with high levels of precarious work and low educational attainment, the vast majority vote (82.5%). The same applies to Baby boomers. With Generation X, voting decreases, become more variable and participation sinks to less than two in three for those with lower educational attainment and high extent of precarious work (62%).

But political marginality and variation across sub-groups is most striking among Millennials. Here, the likelihood of voting is just under 80% for those in non-precarious work and high educational attainment. This drops to 45% among those with low educational attainment and high work precarity. Put in full context, Millennials with high risk of precarious work and lower education attainment vote at half the rate of the average member of the Silent and Baby boomer generations. At the same time, political participation among Millennials in non-precarious work and with higher educational attainment is little different from that of earlier generations.

Political analysts have long recognised that political participation is fundamental for political representation and political equality. Given this, the political implications of precarious work are doubly troubling. Precarious work is concentrated, and increasingly so, among the youngest generation and those with lower socioeconomic status. This in and of itself is bad and has negative consequences within and across generations.

Effective mass mobilisation of young, precarious workers could be a game-changer for almost any election

At the same time, all three factors combine to undermine political participation and contribute to large-scale political inequality which creates both challenges and opportunities. The challenge is the vicious cycle, whereby those that abstain from voting are less likely to have their problems put on the political agenda and there is therefore little political will to change things.

At the same time, a clear opportunity is the demographic reality that effective mass mobilisation of young, precarious workers could be a game-changer for almost any election. For those who want better and more equitable futures for generations to come, it is paramount to figure out ways to re-connect people whose work lives increasingly distance them from political participation.

Professor Ross Macmillan is the Chair in Sociology at the University of Limerick and Leo Azzollini is a PhD candidate in Public Policy and Administration at Bocconi University, Milan

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ