The outlines of the life led by singer Karen Dalton tell a heartbreaking tale. It was one scarred by consistent poverty, intermittent homelessness, bouts of depression and escalating alcohol and drug addiction, culminating in her death from Aids at 55. Yet, to Robert Yapkowitz, who co-directed a new documentary with Richard Peete titled Karen Dalton: In My Own Time, “there’s an inspirational element to her story. Karen was an artist who didn’t compromise. She made music that she was proud of with the people she loved. And that was the focus of her life.”

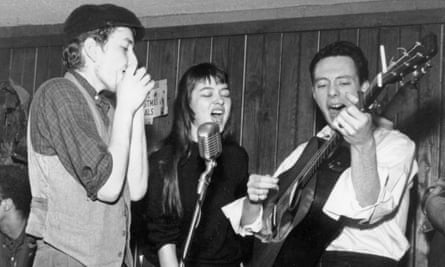

Dalton’s fierce commitment to that music, combined with the razor’s edge she lived on, resulted in recordings of uncommon richness, rarity, and sadness. Unfortunately, the depth of the sorrow in her songs, and the eccentricity of her delivery, made Dalton’s music a tough sell in its day. She performed for three decades but only managed to produce two albums during her lifetime, both released at the start of the 1970s, neither of which rewarded her with more than a peek at fame. Mainly it was fellow artists who recognized her uncommon talent at the time. When her career began on the Greenwich Village folk scene of the early ‘60s she was a respected peer to artists like Fred Neil, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Bob Dylan. In Dylan’s memoir, Chronicles Volume 1, he wrote about first hearing her in a local club. “My favorite singer in the place was Karen Dalton,” he wrote. “She was a tall, white blues singer and guitar player – funky, lanky and sultry. Karen had a voice like Billie Holiday’s and played guitar like Jimmy Reed, and went all the way with it.”

While Dalton’s work may not have connected with general listeners back then, over the past two decades it has been exalted by a new generation, much in the manner of other formerly overlooked artists like Vashti Bunyan and Rodriguez. Several collections of stray demos and live performances have appeared, buttressed by a tribute album on which stars like Lucinda Williams and Patty Griffith set poetry from Dalton’s archives to their own music. The directors of In My Own Time, both of whom are in their 30s, also came to the artist’s music late, driven by their mutual love of outsider artists. What first struck them was the pure sound of her singing. “She used her voice like an instrument,” Yapkowitz said. “It has been compared to a horn.”

Equally striking was her phrasing. Often Dalton let her voice crackle like static, leaving gaps that gave the songs an elliptical feel, attuned to whatever pain or possibility she could find in the lyric. The fitful quality of her phrasing lent her interpretations a sense of surprise, enhanced by her skill at singing around a melody. “When she sings, it sounds like it’s just coming out of her that way,” said the film’s co-director Peete. “But she was constantly perfecting a vocal by recording herself, then listening back to the tapes so she could get just the vocal she wanted.”

The result gave her takes on folk, country and blues songs their own stamp, an important feature given the fact that she almost never wrote her own pieces. Yet, even when she covered God Bless the Child, a song co-written by the singer whose voice hers most resembled, Billie Holiday, Dalton made it speak of her own soul. “Fred Neil once said he saw Karen performing one of his songs so well that if she told him she wrote it, he would have believed her,” Yapkowitz said.

Dalton accompanied herself with a 12-string guitar rather than the more common six-string. “Karen loved Leadbelly, and I think that inspired her choice to play a 12-string,” Yapkowitz said. “She played nearly the same model he did for a while.”

While her brand of bone-dry folk dovetailed with the Greenwich Village scene’s quest for authenticity, she was perhaps the only one in that milieu who had a true folk background. She was raised by strict Southern Baptist parents in Enid, Oklahoma during the dust bowl days. By 16, she was pregnant and married. Three years later, she gave birth again. But she chafed against the conventional life of a housewife and so, by 21, left her husband and two young children to pursue a career in music in New York. “She was a very early feminist,” said Abbe Baird, Dalton’s daughter, in a separate interview for the Guardian. “She went her own way.”

At the same time, the directors said Dalton felt guilt about leaving her kids behind. “There was a huge conflict in her life between being a musician and having to travel and leave her kids,” Peete said. “She struggled with that her whole life.”

When her daughter was five, Dalton brought her to live with her in New York. But it was a tough go for them, since she was living in a dingy tenement apartment that had no functioning toilet. Because she was just a child at the time, Baird said she took it in stride, though tensions did arise from her mother’s mood swings. “She was a lot like her own mother,” she said. “They were both very volatile people – happy and excited one minute, then very depressed and negative.”

Former lovers and fellow musicians in the documentary echo that observation, adding harrowing anecdotes about how Dalton’s mood shifts could lead to violence, amplified by her increasing addictions. “Most of the conflicts she got into were when she was high,” Peete said.

Dalton found more peace when she moved to Colorado, bringing her daughter with her for a rural life they both loved. “She bought me a pony!” Baird recalled.

Eventually, Dalton returned to New York alone, determined to give her career another shot. Gaining traction became difficult, however, given her unwillingness to comprise her flinty sound, intensified by her total lack of interest in playing the role of an entertainer. At one point, she talked with John Phillips about forming a folk group, but her need for control, as well as her purist view of folk, led him to seek the singers with whom he formed the pop-friendly Mamas and the Papas. Dalton finally caught a break in 1969 when she was signed to Capitol Records, which released her unfiltered debut, It’s So Hard to Tell Who’s Going to Love You the Best. A writer for the Village Voice called it “the antithesis of Joan Baez’s boring clarity. It’s plaintive, earthy, insinuating, real. The record makes me feel like crying.”

But it didn’t sell, so Dalton was dropped. A second break came via Michael Lang who, fresh from his success in helping to create the Woodstock festival, was given a label to run. Dalton became one of his first signings, resulting in an album in 1971, In My Own Time, that featured fuller instrumentation and a more accessible sound. Folk-rock mainstay Dino Valenti, who had penned classics like Get Together for the Youngbloods and, later, Fresh Air for Quicksilver Messenger Service, wrote the album’s opening song, Something’s on Your Mind, specifically for Dalton. It’s a masterful creation whose melody ascends without ever finding a resolution, establishing a gripping dynamic that’s echoed by a vocal from Dalton that cascades like smoke. The lyrics Valenti wrote for her nail the singer’s resistance to the machinations of fame (“you can’t make it without ever even trying”), as well as her mental issues and addictions (“saw how you turn your days into night times”). To promote the album, Lang booked this inward-looking folkie as the opening act for a tour headlined by one of the most animated live bands of all time, Santana. “It was a bizarre choice,” said Yapkowitz. “It obviously didn’t work, in part because of the audience and in part because Karen wasn’t able to perform at that arena level.”

According to her friends, the failure of the tour broke her personally and ended any shot at a larger career. From there, her periods of depression increased and the drug use skyrocketed. Her friend, the musician Lacy J Dalton, got her into rehab, but she bolted after two days. Her daughter, who saw little of her mother in her later years, surmises that she got Aids by sharing needles. She died in 1993 in Woodstock, where she had been living for some time in a mobile home.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t the end of the sadness in her story. Dalton left hundreds of cassette tapes of her rehearsals and performances in a shed that one day caught fire, reducing all of them to ash. Later, a second fire consumed journals she had kept over the years that were filled with poetic diary entries and potential song lyrics. Luckily, the film-makers managed to shoot most of the journals’ contents for their documentary during the seven-year span of filming. Key passages from her diaries appear in the film, and they capture both her peaks and her pain. One of the most heartbreaking reads: “My heart is a jackhammer drilling, tearing up the pavement of people’s lives. Muscle contracting trying to contain the pieces. Behind my eyes the throbbing warns.”

In the years since Dalton’s death, several film-makers have approached Baird about a possible documentary. But none of them found the wealth of vintage footage featured in the new film. More, said Baird, “they all wanted to put their own spin on things.”

Lots of fanciful stories have circulated about her mother during that time. “There were rumors that she was a Cherokee Indian princess,” Baird laughed. (Dalton’s father did have some native American heritage).

Though Baird finds the film a fair and accurate depiction of her mother, she and the directors admit that there are gaps in the story. “It’s like trying to make a movie out of Lord of the Rings,” she said with a laugh. “You can’t fit everything in.”

Missing from the film, too, is any word of Dalton’s son, who communicated with the directors but would not appear on camera. They said he has had addiction problems and is “off the grid”. Baird hasn’t heard from him in years.

Ultimately, the full details of Dalton’s life interested the directors less than what they consider the essence of it. “What I want people to understand is that Karen was a person, not just a one dimensional, self-destructive character,” Yapkowitz said. “Through her journals and music, and the stories told in the film by her friends, you can see that there was far more substance in her than people know.”

Karen Dalton: In My Own Time is released in US cinemas on 1 October with a UK date to be announced